Colombian refugees in Ecuador, trying to adapt, recall horrors that drove them from home

Colombian refugees in Ecuador, trying to adapt, recall horrors that drove them from home

Thousands of Liberians who returned from Sierra Leone in 1999 are now facing renewed conflict and displacement.

IBARRA, Ecuador (UNHCR) - When Rosa lit four candles on a sidewalk in this town near the Colombian border last December 8, she got some highly suspicious looks from her neighbours.

"On that day in Colombia we light a candle for every person in the house, put it outside and make a wish," explained Rosa. "But people here didn't know what we were doing. One lady asked me if I was practising witchcraft."

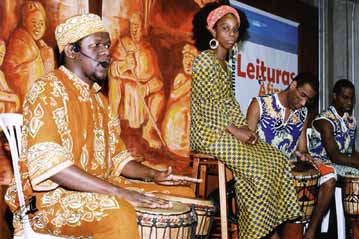

One of 3,000 Colombians seeking refuge in Ecuador, Rosa, who asked that her real name not be used, still marvels at how different life can be here even though the two countries share a 590-kilometre border. "The food is different, the music is different, and we have lots of different customs," she said. "But we take our traditions with us wherever we go, we carry them in our souls."

Tradition was about the only thing Rosa, her two daughters, and a son-in-law brought with them just over a year ago when they left El Moro, a small island in the Pacific Ocean that is attached to the Colombian mainland by a causeway. The family was forced to leave their once quiet beach town because it had become a battleground between the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the country's major guerrilla faction, and right-wing paramilitary groups.

For Rosa and her family, the change was drastic. Her eldest daughter, Carla, went from being the owner of a successful computer-training centre to trying to sell trinkets on the streets of Ibarra. Carla's boyfriend was an officer in the Colombian army. "The FARC told me I either had to turn him over or get lost," she said.

Colombia's 40-year-old internal conflict has left 200,000 people dead, created more than two million internally displaced persons since 1985, and forced tens of thousands of people like Rosa and Carla to flee to neighbouring countries, the United States, and Europe.

There are currently some 3,000 Colombians seeking refuge in Ecuador, almost half of whom live in this colonial city less than 100 kilometres from the Colombian border. Most of the refugees living here left after receiving direct threats on their lives from either the guerrillas or the paramilitary groups.

Fernando's story, for example, is all too common in Ibarra, where many of the refugees have settled because of the town's proximity to Colombia and its long history of commerce with its troubled neighbour.

His boss in the town of Buga, a highly successful real-estate developer and builder, refused to pay the FARC protection money, a common demand by the guerrilla group. Last Fall, when 35 alleged FARC members were found dead in an area Fernando's boss was developing, he was immediately suspected by the guerrilla group of being behind the killings.

"On November first at about five-thirty in the afternoon they shot my boss 35 times and the engineer that was with him 15 times," recalled Fernando, who like the other refugees asked that his real name not be used. The guerrillas killed another four people at the funeral, and later assassinated the man's mother, his two brothers, and two other people working for him.

Three weeks after the first killings, two men approached Fernando and warned him that he too was on the list. "They told me I was a marked man and that I had to get lost now," he recalled.

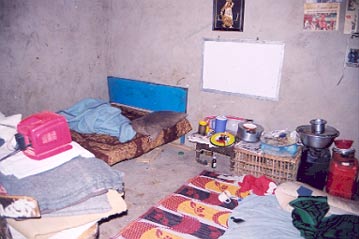

Fernando crossed the border the next day and then sent for his wife and four kids. In Ibarra they stayed at the UNHCR shelter until they found a room to live, and he is now helping his wife cook and sell the baked beans that have been a hit with the Colombian refugees here.

Other refugees, such as Mario, were caught between the FARC guerrillas and the paramilitary troops.

Only a few years ago, Mario - not his real name - was fumigating and harvesting coca fields controlled by the FARC guerrillas in Colombia's Putumayo Province. "It was really the only thing you could do there," the 26-year-old explained. "Of course, I had a vegetable patch, but I had to do that other thing to make money."

But in November 1999, according to Amnesty International, a group of 50 right-wing paramilitary troops entered the town of El Placer where Mario lived, killed 12 villagers and left their bodies in the barren fields surrounding the town.

Mario took his wife and two kids to another village, but trouble followed. One morning, he said, armed men broke into his neighbour's house, who had also fled the Putumayo area, and "disappeared her." It was enough to convince him to leave everything behind but his family.

Today, Mario is trying to forget the past. On this sunny Thursday afternoon, he is pacing in front of the UNHCR building in Ibarra along with 15 other Colombian refugees and asylum seekers waiting to get picked up by a bus that will take them to a new job and, hopefully, a new life.

As part of a pilot project between UNHCR and the private sector, the refugees were given a three-month contract to work on a rose farm on the outskirts of Quito, the Ecuadorian capital. They are provided with accommodations, meals, and health care along with the minimum wage of $130.00 a month. If their contracts are extended, the refugees will automatically be enrolled in the country's social security programme, and receive the same benefits as any Ecuadorian citizen.

For many of the refugees, the job is the first they have been able to find since arriving in Ecuador.

"If it goes well - and there's no reason it shouldn't - we have two other companies that are interested in hiring refugees," said project assistant Ivan Saransig, referring to a second flower farm and a metal shop that approached UNHCR about hiring help.

The project has given the refugees hope, most of whom share Fernando's view of their current situation.

"I am very happy to be in Ecuador right now, but I have to tell you I would love to go back to Colombia sometime," he said. "But at the moment that would be suicide."

By Jim Wyss